The Opium War fought between Britain and China from 1839 to 1842 stands as one of the most consequential clashes of the 19th century, a war that dramatically altered the course of history for both nations. At its core, this conflict was about much more than drugs — it was about trade imbalances, imperial ambitions, and a collision of vastly different cultures and political systems. The story of the Opium War is intricately linked to Britain’s relentless craving for Chinese tea and the dark underbelly of the opium trade that Britain exploited to feed its imperial appetite.

Understanding the full scope of this war reveals the complexity of colonial power dynamics, the socio-economic upheaval in China, and the brutal realities of 19th-century global trade. This article delves deep into the origins, events, and long-lasting consequences of the Opium War, revealing why it remains a stark reminder of imperial exploitation and the human cost of greed.

The Origins of Anglo-Chinese Trade Tensions: The Tea Obsession and Silver Drain Crisis

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, tea had transformed from a luxury item into a staple of British daily life. Tea consumption exploded in Britain, symbolizing both sophistication and comfort, with tea gardens and tea parties becoming social institutions. But this widespread demand came with a costly problem: Britain’s trade deficit with China.

China, under the Qing Dynasty, was economically self-reliant and primarily interested in silver as payment for its goods, including tea, silk, and fine porcelain. British manufactured goods, which were traditionally the backbone of trade with other regions, held little appeal in China. This created a trade imbalance where Britain’s silver reserves were steadily drained to pay for Chinese imports.

The flow of silver out of Britain became a major economic concern. Without silver, Britain risked a weakening currency and financial instability. This predicament pushed British merchants and policymakers to search for a commodity that could reverse the silver flow, something highly desirable in China that they could export from British colonies.

The Dark Turn: Opium Emerges as Britain’s Economic Lifeline

Enter opium—the narcotic drug derived from the poppy plant cultivated primarily in British-controlled India. Although illegal under Chinese law, opium had long been used medicinally and recreationally in China, and by the late 18th century, its recreational use was growing rapidly.

British traders realized opium could be the answer to their silver dilemma. By growing vast opium crops in India and smuggling it into China, they found a commodity that was in soaring demand. British merchants rapidly expanded the opium trade, taking advantage of weak enforcement and rampant corruption among some Chinese officials who turned a blind eye to the contraband.

The consequences of this trade were devastating. By the 1830s, millions of Chinese were addicted to opium. Addiction ravaged families and communities, sapping productivity and exacerbating social instability. Opium addiction spread so fast and extensively that it became a national crisis, threatening the very fabric of Chinese society.

China’s Response: Lin Zexu and the Determined Crackdown

Recognizing the catastrophic impact of opium, the Qing Emperor appointed Lin Zexu in 1839 as the special imperial commissioner with the urgent task of ending the opium scourge. Lin was known for his integrity, intelligence, and unwavering dedication to justice.

Upon arriving in Guangzhou, the main trading port between China and foreign merchants, Lin launched a fierce campaign against opium. He demanded the surrender of all opium stocks from British traders and enforced strict penalties on anyone involved in the trade.

In a dramatic and symbolic act, Lin confiscated and destroyed over 20,000 chests of opium, worth millions of pounds, dumping the narcotic into the South China Sea. Lin’s uncompromising approach was a bold statement of China’s sovereignty and a refusal to tolerate foreign exploitation any longer.

However, the British merchants and government saw Lin’s actions as a direct challenge to their profits and national prestige. Britain, underpinned by a belief in free trade and mercantilism, was unwilling to back down from its lucrative opium business.

The Clash of Empires: From Trade Disputes to Full-Scale War

The destruction of opium stocks was the spark that ignited a broader conflict. Britain, already expanding its global empire and determined to maintain economic dominance, interpreted Lin’s crackdown as an affront requiring military response.

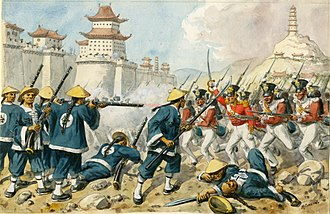

In late 1839, Britain dispatched naval forces to China’s southern coast, initiating the hostilities. British warships, armed with steam power and advanced artillery, quickly overwhelmed Chinese defenses, which relied on outdated ships and traditional military tactics.

The war was marked by a series of British victories, as they captured key ports, including the strategically vital Pearl River Delta and the island of Hong Kong. The British navy’s technological edge gave it a decisive advantage, exposing the Qing Dynasty’s military weaknesses.

China’s attempts to negotiate peace failed as Britain insisted on terms favorable to its interests. The Qing government found itself trapped between a desire to end hostilities and the need to defend its sovereignty.

The Unequal Treaty: The Treaty of Nanking and Its Far-Reaching Consequences

The war ended in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking, a landmark document that forced China into humiliating concessions. The treaty’s terms were heavily skewed in Britain’s favor and marked the beginning of a new era of foreign dominance in China.

Hong Kong was ceded to Britain as a permanent colony, turning it into a strategic hub for British trade and military presence in East Asia. Five Chinese ports—Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai—were opened to British merchants under favorable conditions.

Additionally, the treaty granted extraterritorial rights to British citizens in China, meaning they were subject to British law, not Chinese law, when in treaty ports—a blatant infringement on Chinese sovereignty.

China also agreed to pay a massive indemnity to Britain, further draining its treasury, and to legalize the opium trade, effectively accepting the drug’s destructive presence.

The Treaty of Nanking is often described as the first of the “unequal treaties,” setting a precedent for other Western powers like France and the United States to demand similar privileges.

Imperial Ambitions Beyond Trade: Britain’s Broader Strategic Motives

While trade interests were the immediate cause, the Opium War also reflected Britain’s wider imperial ambitions. The British Empire sought to consolidate power in Asia, expand its colonial footprint, and control vital maritime trade routes.

The acquisition of Hong Kong was not just about trade but about establishing a strategic military base. Control over parts of China allowed Britain to exert political influence and project power throughout the region.

Britain’s insistence on “free trade” was less about ideology and more about securing unfettered access to markets and resources. The Opium War demonstrated how economic interests could be backed by military force to open new territories and control valuable commodities.

The Chinese Experience: Societal Upheaval and National Trauma

For China, the Opium War was a national catastrophe. Beyond the immediate military defeat and territorial losses, it symbolized the failure of the Qing government to protect its people and sovereignty.

The opium epidemic left deep scars, with millions suffering from addiction and its social consequences. The Chinese population faced poverty, social disintegration, and a crisis of governance.

The war also exposed China’s technological backwardness, prompting some officials to call for reforms. However, deep-rooted conservatism and factionalism within the Qing court hampered meaningful change.

The Opium War planted the seeds of nationalist resentment against foreign powers, a sentiment that would fuel future uprisings, reforms, and the eventual fall of the Qing Dynasty.

Global Impact and Legacy: Shaping Modern Sino-Western Relations

The Opium War had a profound global impact. It was a turning point in East-West relations, marking the beginning of Western imperial dominance in China and the wider Asia-Pacific region.

The “Century of Humiliation” that followed saw China subjected to further invasions, unequal treaties, and territorial losses. This period shaped Chinese national identity and informs modern China’s foreign policy and its sensitivity toward sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The war also sparked debates in Britain and other Western countries about imperial ethics, trade policies, and the consequences of addiction. The opium trade, once celebrated as a source of wealth, came under scrutiny as the human cost became undeniable.

Human Cost and Historical Reflections: The Price of Empire

Looking back, the Opium War serves as a cautionary tale about the destructive consequences of imperial greed and economic exploitation. Millions of lives were devastated by addiction, families torn apart, and a sovereign nation forced to bow to foreign demands.

The conflict highlights the dangers of cultural arrogance and the imposition of foreign values without respect for local laws and traditions. Britain’s actions, justified by economic interests, inflicted long-lasting damage on China’s society and governance.

Today, the Opium War is remembered not only as a military conflict but as a symbol of the complex interplay between commerce, power, and morality in global history.